Overall, global inequality has been decreasing over the last several decades. That may contrast with the rhetoric about inequality that you are familiar with from the media. However, the global decrease in inequality has mostly been driven by the substantial rise in incomes in China. However, China's contribution to decreasing global inequality may be about to change. In a new working paper, Ravi Kanbur (Cornell University), Eduardo Ortiz-Juarez and Andy Sumner (both King’s College London), discuss the possibility of a 'global inequality boomerang'.

Focusing on between-country inequality (essentially assuming that within-country inequality doesn't change), and using a cool dataset on the income distribution for every country scraped as percentiles from the World Bank's PovcalNet database, Kanbur et al. find that:

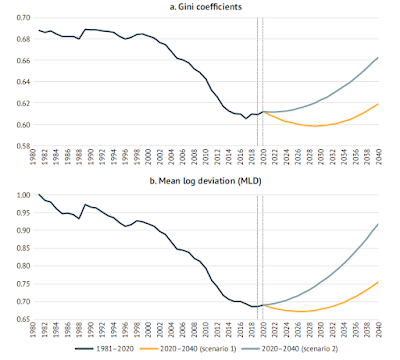

...there will be a reversal, or ‘boomerang’, in the recent declining (between-country) inequality trend by the early-2030s. Specifically, if each country’s income bins grow at the average annual rate observed over 1990–2019 (scenario 1), the declining trend recorded since 2000 would reach a minimum by the end-2020s, followed by the emergence of a global income inequality boomerang...

This outcome is illustrated in their Figure 4, which shows the historical decline in inequality since the 1980s, along with their projections forward to 2040:

Scenario 1 assumes an almost immediate return to pre-pandemic rates of growth. Scenario 2 assumes slower growth rates for countries with lower rates of vaccination. Neither scenario is particularly likely, but the future trend in global inequality is likely to be somewhere between them, and likely to be moving upwards. Why is that? Between-country inequality has been decreasing as China's average income has increased towards the global average. In other words, Chinese household incomes have increased, decreasing the gap between Chinese households and households in the developed world. However, once China crosses the global average, further increases in Chinese average income will tend to increase between-country inequality.

Of course, this might be a pessimistic take, because if other populous poor countries (including India, Indonesia, Pakistan, Nigeria, and Ethiopia) grow more quickly, then their growth might reduce inequality enough to offset the inequality-increasing effect of Chinese growth. However, that is a big 'if'. According to World Bank data, China's GDP per capita growth rate averaged 8.5 percent per year between 1991 and 2020. Compare that with 4.2 percent for India, 3.2 percent for Indonesia, 1.5 percent for Pakistan, 1.4 percent for Nigeria, and 3.9 percent for Ethiopia. These other countries would have to increase their growth rates massively to offset Chinese growth's effect on inequality.

This isn't the first time that Chinese growth has been a concern for the future of global inequality. Branko Milanovic estimated back in 2016 that China would be contributing to increasing global inequality by 2020 (see my post on that here). Things may not have moved quite that quickly (a pandemic intervened, after all). Kanbur et al. are estimating under their Scenario 1 that the turning point will be around 2029 (and around 2024 under their Scenario 2). Slower Chinese growth, and faster growth in the rest of the world, have no doubt played a part in this delay. However, it's likely that the turning point in global inequality cannot continue to be delayed for much longer.

Read more:

No comments:

Post a Comment