Inflation is defined as a general increase in the price level. Right now, across the rich OECD countries, we are in a period of historically high inflation. The inflation rates in the US and the UK are both over 8 percent, and in New Zealand the inflation rate was 7.3 percent to the end of June (a 32-year high).

What causes prices to rise? Prices are determined in markets, and in the simplest supply and demand model of the market, an increase in equilibrium prices can be caused by a decrease in supply, or an increase in demand (or both). [*] [**] In the current inflationary period, supply may have decreased because of supply chain disruptions, while demand may have increased because of wage subsidies and other government responses to the pandemic.

That raises the question: how much of the current high inflation is driven by decreasing supply, and how much by increasing demand? That is the question that Adam Hale Shapiro looks at in this FRBSF Economic Letter, published in June. Shapiro first separates items in the personal consumption expenditure basket (used to measure inflation in the US) into those that are supply-driven and those that are demand-driven. As he explains:

Demand-driven categories are identified as those where an unexpected change in price moves in the same direction as the unexpected change in quantity in a given month; supply-driven categories are identified as those where unexpected changes in price and quantity move in opposite directions. This methodology accounts for the evolving impact of supply- versus demand-driven factors on inflation from month to month.

This categorisation is what we would expect from a supply and demand model of markets. An increase in demand increases the equilibrium price and the equilibrium quantity. A decrease in supply increases the equilibrium price, but decreases the equilibrium quantity. When the quantity doesn't change, it may be that both increase in demand and a decrease in supply are happening (and Shapiro labels those cases 'ambiguous').

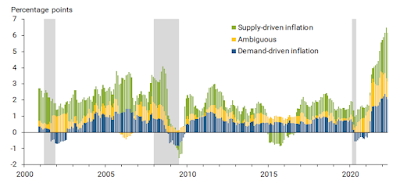

Then, armed with this categorisation, separating the overall inflation rate into the proportion coming from by demand-driven categories, and the proportion coming from supply-driven categories, is relatively straightforward. The overall picture going back to 2000 looks like this:

Notice that both sources of inflation fluctuate quite a lot, but that demand-driven inflation (the blue bars) fluctuates less than supply-driven inflation (the green bars). Note that recessions (the grey bands in the figure) tend to be characterised by demand-driven deflation (at least after the mid-point of the recession). You can also see the rapid increase in inflation in recent months, and that it has both supply-driven and demand-driven causes (as well as a large increase in ambiguous causes (the yellow bars)). However, the change in supply-driven inflation is larger than the change in demand-driven inflation. As Shapiro notes:

Supply-driven inflation is currently contributing 2.5 percentage points (pp) more than its pre-pandemic average, while demand-driven inflation is currently contributing 1.4pp more. Thus, supply-driven inflation explains a little more than half of the 4.8pp gap between current levels of year-over-year PCE inflation and its pre-pandemic average level. Demand factors explain a smaller share of elevated inflation levels, accounting for about one-third of the difference. The ambiguous category, which is not shown, explains the remainder of the difference.

It would be interesting to see whether the relative contributions of supply-driven inflation and demand-driven inflation are the same in other OECD economies, and whether differences in the drivers of inflation explain the milder inflation being experienced in some countries, when compared with others.

[HT: Marginal Revolution]

*****

[*] Which brings me to one of my pet hates. Inflation does not cause increases in prices. Inflation is a summary measure of price changes across the economy as a whole, not a driver of price changes.

[**] Increases in market power could also cause increases in prices in particular markets. However, it is unlikely that market power would increase sufficiently and simultaneously in enough markets to have an appreciable effect on inflation, despite anything you may have read. Although, market power might exacerbate changes in the inflation rate.

No comments:

Post a Comment